When my mother was fourteen a book was given to her appetite for reading and need to escape her own complicated narrative. Published by Random House, New York, it was wider and “taller” than it was thick, bound in dark blue-green with a slightly gullied joint and gold lettering on a strong spine, front and back boards illustrated by the work of Fritz Eichenberg, more of his moodily magnificent wood engravings within. Monotype Bodoni with long descenders and double-columns presented its text, chapters running on without pause, like the brave and breathless mind and spirit that filled it with one of the most mercilessly compelling, passionate, earthy unearthly stories ever told.

When my mother was fourteen a book was given to her appetite for reading and need to escape her own complicated narrative. Published by Random House, New York, it was wider and “taller” than it was thick, bound in dark blue-green with a slightly gullied joint and gold lettering on a strong spine, front and back boards illustrated by the work of Fritz Eichenberg, more of his moodily magnificent wood engravings within. Monotype Bodoni with long descenders and double-columns presented its text, chapters running on without pause, like the brave and breathless mind and spirit that filled it with one of the most mercilessly compelling, passionate, earthy unearthly stories ever told.

Over twenty years later this classic hardcover edition of Wuthering Heights was re-gifted to me and my reading the Brontës began with Emily. She immediately and irrevocably enticed me out of 1960s suburban America, away from fenced-in yards, narrow sidewalks, and managed nature, into the wilderness of her West Yorkshire world, inexhaustible imagination and uncompromising soul. I had never before read a novel as descriptive and dramatic, bold and mesmerizing, as validating of my own mystic inclinations. Of course, I hadn’t. I was twelve.

Fritz Eichenberg Illustration for 1943 Edition of Wuthering Heights

It was never easy to tell what was stirring in Emily’s heart. That afternoon her touch and words felt like pleading, as much as she could ever be suppliant. It might change Anne’s view of her nearest and dearest sibling. Even walking physically tall and strong across the moors, Emily seemed smaller, as if her influence was shrinking.

~ Without the Veil Between © 2017 DM Denton

Today, July 30, 2017 marks the 199th anniversary of the birth of Emily Brontë.

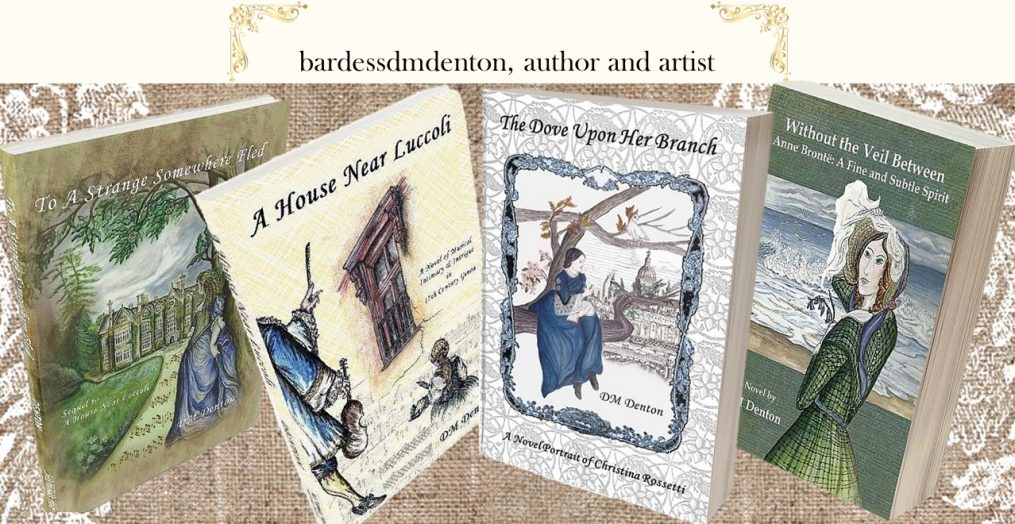

As many of you are already aware, my novel about her youngest sister, Anne – Without the Veil Between, Anne Brontë: A Fine and Subtle Spirit – is finished and awaiting publication by All Things That Matter Press later this year.

As many of you are already aware, my novel about her youngest sister, Anne – Without the Veil Between, Anne Brontë: A Fine and Subtle Spirit – is finished and awaiting publication by All Things That Matter Press later this year.

Emily was an important presence in Anne’s life as Anne was in hers. In 1833, when Emily was fifteen and Anne thirteen, friend of the family Ellen Nussey noted, on a visit to Haworth, they were “like twins – inseparable companions … in the very closest sympathy, which never had any interruption.” A few years earlier, in the interval between Charlotte going away to school and Emily joining her, Anne and Emily had liberated themselves from their older sister and brother Branwell, especially in their writings, to create their own fantasy world. Set in the North Pacific, it consisted of at least four kingdoms: Gondal (how their juvenilia is usually referenced), Angora, Exina and Alcona. (“None of the prose fiction now survives but poetry still exists, mostly in the form of a manuscript donated to the British Museum in 1933; as do diary entries and scraps of lists” – Wikipedia).

“I must have your opinion, Anne.” Emily abruptly moved Tiger from her lap, swung her feet off the sofa and slipped them into her shoes before she began to recite, “‘In the dungeon-crypts idly did I stray, reckless of the lives wasting there away; Draw the ponderous bars! open, Warder stern!’” She stood and stamped. “‘He dared not say me nay—the hinges harshly turn.’”

~ Without the Veil Between © 2017 DM Denton

The first known reference to the Gondal Saga is in their also joint diary paper of 1834 (below as originally written):

Anne and I have been peeling apples for Charlotte to make an apple pudding . . . Taby said just now come Anne pillopuate a potato Aunt has come into the kitchen just now and said where are you feet Anne Anne answered on the on the floor Aunt papa opened the parlour Door and said B gave Branwell a Letter saying here Branwell read this and show it to your Aunt and Charlotte – The Gondals are discovering the interior of Gaaldine. Sally mosley is washing in the back kitchin.

In her biography of Anne, Winifred Gerin writes “Unlike Charlotte’s and Branwell’s Angria … the permanence of Gondal lay in the fact that it was not a world at several removes from reality but only a slightly blurred print of the landscape of home.”

It was the Haworth moors that inspired the poetry of Gondal. Gerin writes: “To Emily, nature became an end in itself; to Anne, a pathway to God; to both of them a necessity.”

Anne, in one of her Gondal poems (Z ———‘s Dream), surely expressed the experience and essence of both their spirits:

I loved free air and open sky

Better than books and tutors grim,

And we had wandered far that day

O’er that forbidden ground away –

Ground, to our rebel feet how dear;

Danger and freedom both were there! —

Had climbed the steep and coursed the dale …

Ellen Nussey was not altogether correct when she claimed Emily and Anne’s closeness “never had any interruption”. Physical separations, caused by periods away at school and governess stints, especially Anne’s briefly at Blake Hall and then for five years at Thorpe Green forty miles from Haworth, were bound to test their unity. As they left their childhood behind and stumbled into womanhood, Anne’s maturing sense of duty, hope for self-sufficiency, not always pleasant experience of “the world” and literary insistence for speaking truth over indulging in fantasy left less time and inclination for the Gondal prose and poetry Emily continued to feel enthusiastic about.

Why should Anne be guided by Emily, differences in temperament, experiences, and responsibilities challenging their cohesion? How could she not? Even when her closest sister was miles away she was present in spirit. The phantom bliss, as Emily called her imagination, had once cast a spell on Anne, but the clingy little sister had become self-reliant and more rooted in reality. If Anne was truthful, she did envy Emily settled at Haworth, never having to apologize for withdrawing from the world and into her writing.

~ Without the Veil Between © 2017 DM Denton

In 1842, returning home from Brussels for the Christmas holiday, Emily exerted her independence in the opposite way Anne did and was more adamant than ever to stay humbly domestic and wildly imaginative in her own isolated piece of the planet at and around Haworth. She remained there for the rest of her life, never going further away than nearby Keighley, Bradford or Manchester or for longer than a few days as in early summer 1845.

Anne and I went our first long journey by ourselves together–leaving Home on the 30th of June-monday sleeping at York–returning to Keighley Tuesday evening sleeping there and walking home on Wednesday morning–though the weather was broken, we enjoyed ourselves very much except during a few hours at Bradford and during our excursion we were Ronald Macelgin, Henry Angora, Juliet Augusteena, Rosobelle Esualdar, Ella and Julian Egramont Catherine Navarre and Cordelia Fitzaphnold escaping from the palaces of Instruction to join the Royalists who are hard driven at present by the victorious Republicans–The Gondals still flourish bright as ever I am at present writing a work on the First Wars–Anne has been writing some articles on this and a book by Henry Sophona–We intend sticking firm by the rascals as long as they delight us which I am glad to say they do at present.

~from Emily’s diary paper, written on her birthday, July 30, 1845.

Anne drifted in and out of obliging Emily’s desire to spend most of the journey pretending to be Gondal princes and princesses fleeing the palaces of instructions to join the Royalists.

~ Without the Veil Between © 2017 DM Denton

In her paper written on the same date, Anne didn’t mention the York trip and her reflection on Gondal hints, I think, of her trying to hold onto the past mostly for Emily’s sake.

How will it be when we open this paper and the one Emily has written? I wonder whether the Gondalian will still be flourishing, and what will be their condition. I am now engaged in writing the fourth volume of Solala Vernon’s Life.

Emily might argue imaginative escapes were a good defense. One day Anne might return to being as Emily wished her to be, in part if not entirely. For now, Anne needed to concentrate on the practicalities of duty and endurance, and the long-term benefits of maintaining her integrity.

~ Without the Veil Between © 2017 DM Denton

When, in September 1845, Charlotte, whether by accident or design, happened upon the magnificent poems Emily had written and, up until then, kept from her sisters, it was Anne who understood Emily’s anger at having her sacred privacy broken into.

“You robbed me!”

Emily took her tirade to the kitchen, slamming doors, yelling at the dogs, and rattling pots. It was fortunate their father was out and Tabby was almost deaf and knew how to soothe her. Martha was prudent enough not to try.

Anne was exhausted, in part due to the long blustery walk she shared with Emily before they discovered Charlotte’s discovery, not least because she felt the pain of every verbal blow her sisters thrust at each other.

~ Without the Veil Between © 2017 DM Denton

It was also Anne who mediated the battle that ensued between her sisters, a task not made easier by Charlotte’s insistence that Emily’s poetry be published. Poems by Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell – and, subsequently, Wuthering Heights – might never have made it into print if Anne hadn’t offered Charlotte a look at her own verses and somehow softened Emily’s resistance to sharing herself, even under a pseudonym, so publically.

“If you must, publish the poems. But I’ll not be revealed.”

“You mean, your name?” Charlotte took off her glasses, unmasking the strain in her eyes.

“Not any part of me.”

“Noms de plume,” Anne realized with a mixture of relief and regret.

“Hmm.” Charlotte nodded. “As much for hiding our sex as our Emily’s obsession with being invisible.”

“All Gondal references must be removed.” Emily knocked off her shoes. “Yours, too, Annie.”

“Yes, I realize that.”

Emily put her feet on the sofa and her head back. “You need something to do. Both of you. I’m sick of seeing you mope around, one wondering whether she’s loved and the other what God wants her to do.”

“You might try, Em, but you won’t irritate me.” Charlotte returned her poetry to her. “Not while I’m so glad we’re finally all in agreement.”

“I’m submitting, not agreeing, Lotte dear.”

~ Without the Veil Between © 2017 DM Denton

Emily Brontë, from a painting by Branwell Brontë

Love is like the wild rose-briar,

Friendship like the holly-tree —

The holly is dark when the rose-briar blooms

But which will bloom most constantly?

~ from Mild the Mist Upon the Hill by Emily Brontë

For a few moments a full reconciliation between them seemed viable. They stood arm in arm looking into the shrubby, mossy gully washed by winter’s thaw and spring rain streaming off the moors, blue light casting it as fantastical as their imaginations had once been. If they were to continue on, there wasn’t any choice but to follow each other precariously down an uneven and slippery path, water rushing, splashing, and, eventually, falling steeply and musically towards the beck it was destined to join, song birds adding their voices and the rhythm of their wings.

~ Without the Veil Between © 2017 DM Denton

Portrait of the Brontë Sisters, c.1834 (oil on canvas) by Patrick Branwell Brontë, National Portrait Gallery, London,

![]() ©Artwork and writing, unless otherwise indicated, are the property of Diane M Denton. Please request permission to reproduce or post elsewhere with a link back to bardessdmdenton. Thank you.

©Artwork and writing, unless otherwise indicated, are the property of Diane M Denton. Please request permission to reproduce or post elsewhere with a link back to bardessdmdenton. Thank you.