People tend to forget that the word “history” contains the word “story”. ~ Ken Burns

For me, the most seductive historians, whether they teach, write essays or books, or make films, are masterful storytellers. They do not forget individual narratives are the breath of the past. Just as life needs each inhale and exhale, even those that go unnoted, history lives because of each story, even—especially—those that have gone untold.

The common story is 1+1=2. The real genuine stories are about 1+1=3. That thing that matters most is more than the sum of its parts. ~ Ken Burns

Venturing off the beaten path is what creativity thrives on. Going beneath, behind, beyond the obvious is what makes history vital rather than static. Something is missing when it’s defined as 1+1=2, leaving out the imagination to expand the equation. Ken Burns is right; the thing that matters most is missing. Unless the door is kept open to fresh interpretation, history loses its chance to other views, to tell the untold, to add up into more than the sum of its parts. Teaching, writing, making films about history are not just about keeping it alive but letting it live to its fully fleshed out potential.

History is malleable. A new cache of diaries can shed new light, and archeological evidence can challenge our popular assumptions. ~ Ken Burns

Unpublished manuscripts by Charlotte Bronte recently discovered inside a rare book belonging to her mother.

Imagination, curiosity, obsession can shed new light. New diaries and archeological evidence aren’t found by those who are satisfied with what has been discovered, decided, and, worse, decreed to be true. Surely, even for the historian, absolutes are questionably so, because they rarely tell the whole truth but, instead, slam the door on possibility.

Uncertainty is more essential to exploration than certainty.

With enormous respect and endless gratitude for the investigation, dedication, passion for a subject, and expertise of historians (I couldn’t do what I do without them), I feel that in many ways the best historical fiction writers are reflections of the most creative of their nonfiction brethren. They start similarly from interest and instinct, and are driven to take their interest and instinct on a journey, often a long one, that satisfies their need to explore and discover, their hope of getting lost to find the way, their expectation of being surprised, and their compulsion of making something new out of something old.

Truth, we hope, is a byproduct of the best of our stories, and yet there are many many different kinds of truth. ~ Ken Burns

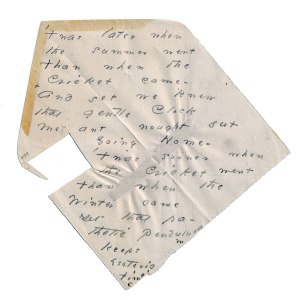

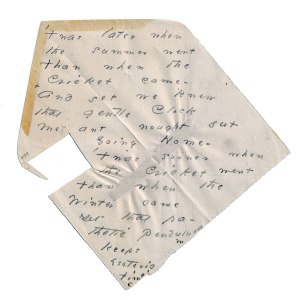

Twas Later When the Summer Went by Emily Dickinson

The kind of truth I look for when writing historical fiction is often found in the little things – The Gorgeous Nothings, as a book of Emily Dickinson’s complete envelope writings in facsimile is titled. They take one intimately into the life of a historical person. As I heard the American historian Doris Kearns Goodwin recently say (not quoting her verbatim): letters and diaries even as they speak of current events often let us into the deepest feelings and thoughts of their authors. Insight and inspiration can come from objects, activities, habits, gestures, all manner of seemingly insignificant things. Somehow they excite me more than epic occurrences. Currently, I’m working on a fiction about Anne Brontë and a wealth of “gorgeous nothings” are not only illuminating her outer world, but offering me a deeper understanding of her inner one. Small things are making the story I’m telling about her so much larger than I initially thought it would be.

Art Print c19th Victorian Barefoot Farm Girl Sits Fireside Fireplace w Cat

I could hear her sigh of relief when I read of her habit of sitting in a rocking chair and propping her feet on the hearth fender in the parlor at Haworth Parsonage—it offered me a glimpse of her ease in her home environment and set the scene for a whole chapter. As a child, answering her aunt’s chastising “where are your feet, Anne?” with a cheeky “on the ground, Aunt”, showed me a girl—who grew into a woman—as spirited as she was dutiful. A diary entry by Emily describing her and Anne’s lazy start to the day offers the reminder that normalcy was as much a part of their lives as drama and tragedy and shows their home, so often depicted holding them in dismal isolation, as a playful everyday place: “It is past Twelve o’clock {sic} Anne and I have not tidied ourselves, done our bedwork or done our lessons and we want to go out to play …”

A seemingly trivial incident revealed much about Roger North, a historical character featured in my novel To A Strange Somewhere Fled. In his book Notes of Me he describes the effect entertaining “30 gentlemen” at Wroxton had on him by the end of the evening, revealing his reserve in the extreme when he was forced into pretentious social activity: “I made my way like a wounded deer, to a shady moist place, laid me downe {sic}, all on fire as I thought myself, on the ground; and there evapourated [sic] for 4 or 5 hours, and then rose very sick, and scarce recovered in some days.” (I know the feeling!)

His reflection on which instrument was best for women to play was another delicious morsel of insight into him as man who liked a certain amount of order, as well as modesty in women: “…the harpsichord for ladies rather than the lute; one reason is it keeps their body in a better posture than the other, which tends to make them crooked.”

Nicole Kipar 1688

Orazio Gentileschi 1625

(The) history of private men’s lives (is) more profitable than state history. ~ Roger North

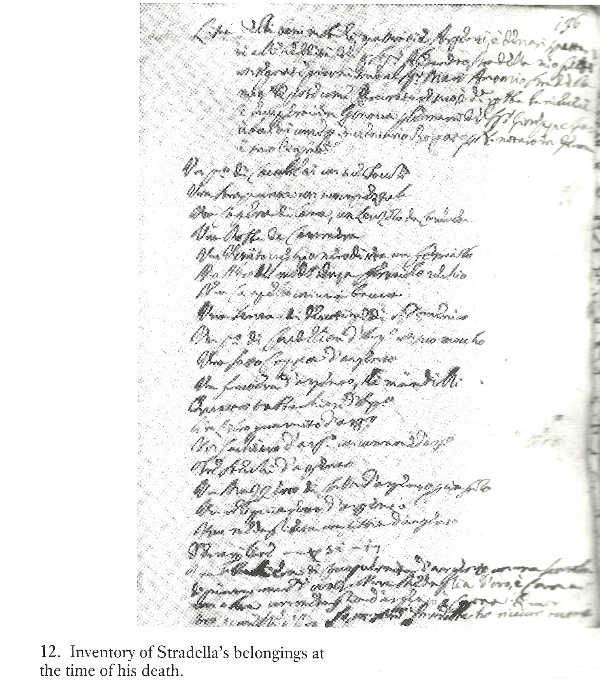

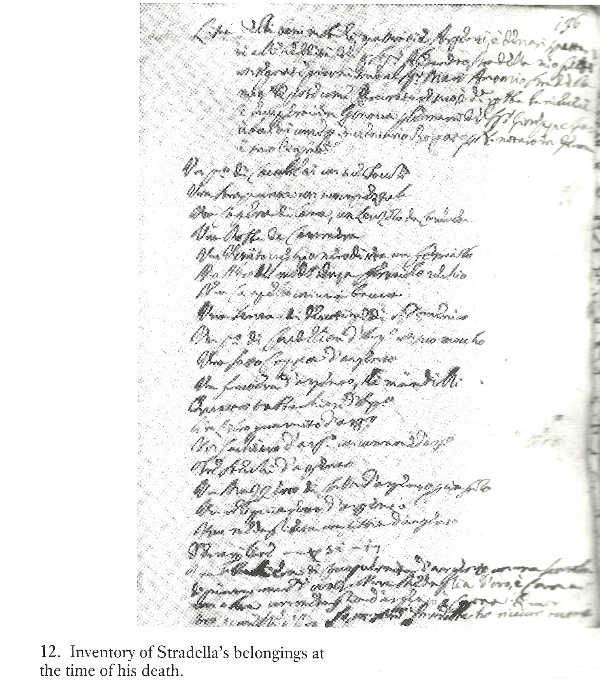

It was a list of Alessandro Stradella’s possessions at the time of his death that gave me a starting point for my novel A House Near Luccoli and the fictional Donatella a way to become personally acquainted with him before he physically came into her life (the latter an advantage she had over me), revealing a man who loved beautiful things and yet hinting at a roughness around the edges (and possibly a self-penance for his misdeeds?) through the anomaly of the hemp and wool bedding on the list of silver and gold and diamonds and silk.

With no portraits or descriptions of Stradella’s physical appearance, almost nothing recorded of his personality, I found him in the paradox between the masterpieces and messes he made. Additionally, I listened for him in the music he composed and saw something of his grace and nobility, but, also, his flair and pride (and over-confidence?) in his signature.

I’m often “delayed” in my writing by always looking for more magnificently mundane things. I can’t help myself. I’m more fascinated by the focused rather than panoramic view, squinting my literary eyes to see into shadows; and risk remaining in them myself.

I also realize that for a writer to enter completely into a story, to offer much more than 1+1=2, there must be a goal–at least a goal–to leave no stone unturned.

As a historian, what I trust is my ability to take a mass of information and tell a story shaped around it. ~ Doris Kearns Goodwin

As an author of historical fiction, I can say the same. Perhaps, I will be an unadulterated historian in my next life. As long as I can be an accomplished musician, too!

![]() ©Artwork and writing, unless otherwise indicated, are the property of Diane M Denton. Please request permission to reproduce or post elsewhere with a link back to bardessdmdenton. Thank you.

©Artwork and writing, unless otherwise indicated, are the property of Diane M Denton. Please request permission to reproduce or post elsewhere with a link back to bardessdmdenton. Thank you.